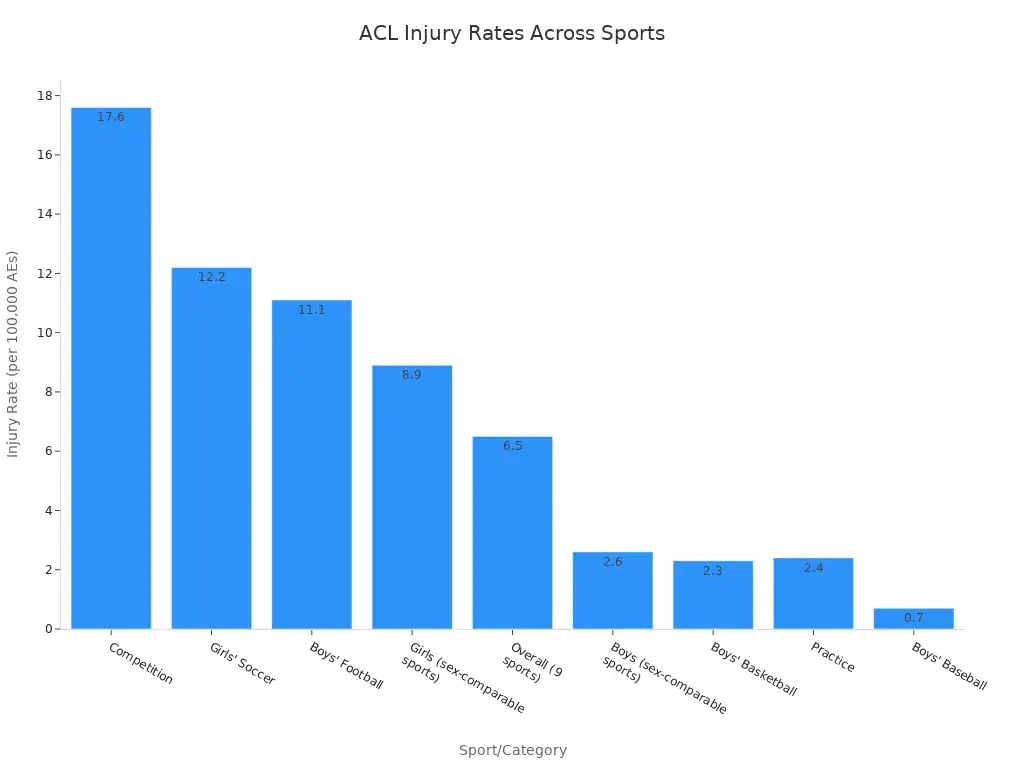

Knee ligaments are strong bands of tissue. They connect bones in the knee. These ligaments provide stability to the knee joint. The four main types of knee ligaments are the ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL. This post explores each one. Understanding these structures is important for overall knee health and injury prevention. ACL injuries are common, especially in competitive sports. Girls in sex-comparable sports experience higher ACL injury rates than boys.

Key Takeaways

Knee ligaments are strong tissues. They connect bones in the knee. They keep the knee joint stable.

The four main knee ligaments are ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL. Each ligament has a special job to control knee movement.

ACL and PCL control front-to-back knee movement. MCL and LCL control side-to-side knee movement.

Ligament injuries are common, especially in sports. They can cause pain and instability. Recovery depends on how bad the injury is.

Understanding knee ligaments helps prevent injuries. It also helps in getting the right treatment if an injury happens.

What are Knee Ligaments?

Defining Ligaments in the Knee

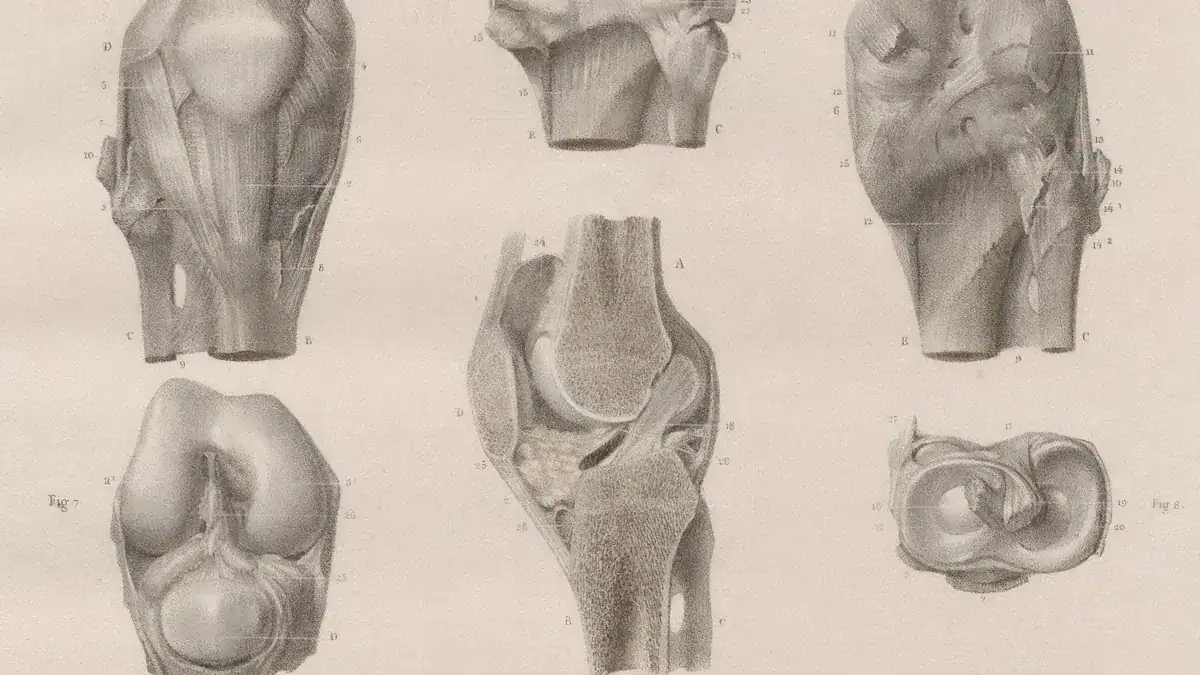

Knee ligaments are strong, fibrous bands of tissue. They connect bones within the knee. Specifically, these ligaments link the thigh bone (femur) to the lower leg bones (tibia and fibula). Ligaments have a special structure. They contain parallel bundles of collagen fibers.

This design allows them to efficiently transfer force between bones along their length. Their unique elasticity helps them facilitate smooth movement in the knee joint under normal conditions. They also restrict excessive joint movement when the knee experiences high forces.

Their Crucial Role in Knee Stability

Ligaments play a vital role in maintaining the stability of the knee. They enhance and maintain joint stability during movement. They also limit motion beyond the knee’s normal range. The knee ligaments work together to prevent unwanted movements.

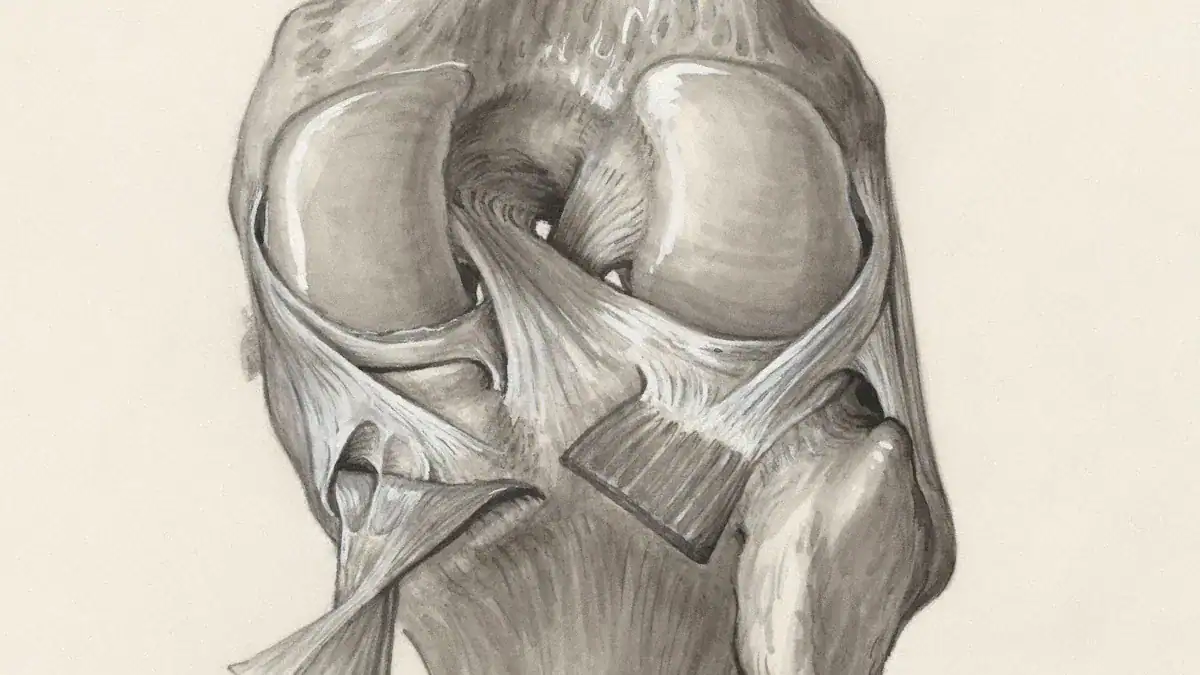

Cruciate Ligaments (ACL, PCL): These ligaments restrict the knee joint’s forward and backward movement. The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) primarily stops the lower leg bone from sliding too far forward. It also helps control rotation. The Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) mainly prevents the lower leg bone from sliding too far backward.

Collateral Ligaments (MCL, LCL): These ligaments constrain the knee’s side-to-side motion. The Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) is on the inside of the knee. It resists forces that push the knee inward (valgus stress). The Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) is on the outside of the knee. It resists forces that push the knee outward (varus stress).

Each ligament has specific jobs to keep the knee stable:

Ligament | Primary Function |

|---|---|

Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) | Resists varus stress |

Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) | Resists valgus stress |

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) | Primary restraint to anterior translation; plays a role in axial rotation |

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) | Primary restraint to posterior translation |

These knee ligaments work together. They ensure the knee moves correctly and stays strong during daily activities and sports.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

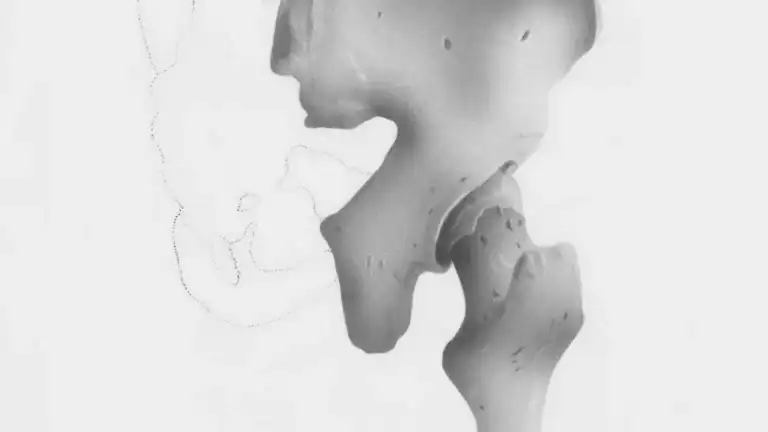

ACL Location and Anatomy

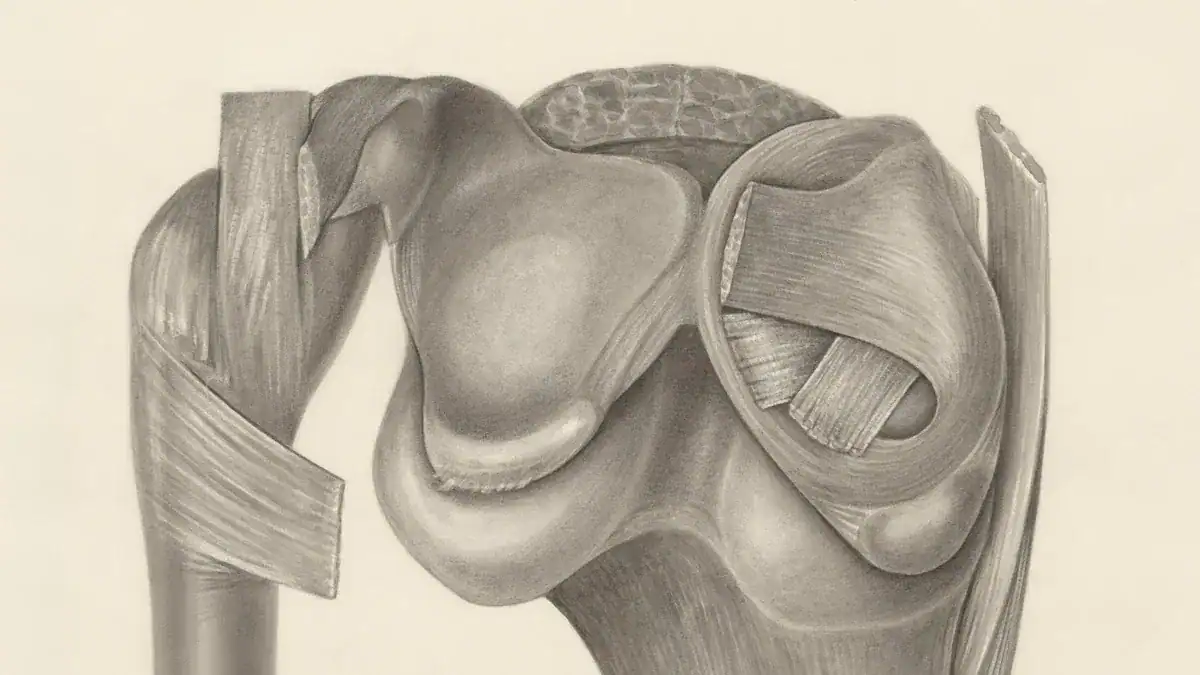

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most well-known ligaments in the knee. It sits deep inside the knee joint. The ACL crosses diagonally from the back of the thigh bone (femur) to the front of the shin bone (tibia). This crossing pattern gives it the name “cruciate,” meaning cross-shaped.

The ACL has specific attachment points. On the femur, it attaches to the posteromedial corner of the lateral femoral condyle. This area is part of the intercondylar notch. On the tibial side, the ACL inserts into a fossa located in front of and lateral to the anterior spine. Each bundle of the ACL has distinct footprints on the tibial side.

ACL Function

The primary role of the ACL is to provide stability to the knee. It mainly prevents the shin bone (tibia) from sliding too far forward on the thigh bone (femur). This is known as anterior tibial translation.

The ACL contributes significantly to resisting this movement, providing about 85% of the restraining force against anterior tibial displacement at both 30 and 90 degrees of knee flexion. The ACL also helps control rotational movements of the knee.

It has two main bundles: the anteromedial bundle (AMB) and the posterolateral bundle (PLB). The AMB primarily controls anterior tibial translation when the knee is bent (in flexion). The PLB resists anterior tibial translation when the knee is straight (in extension).

Common ACL Injuries

ACL injuries are common, especially in sports. Many ACL tears happen without direct contact. These non-contact injuries often involve multiplane knee loadings. This means the knee experiences forces from several directions at once. Activities like landing from a jump or sudden deceleration can cause an ACL injury.

Changing direction quickly, with or without deceleration, also poses a risk. Sometimes, the knee goes into a valgus position (knock-kneed) with rotation while it is nearly straight or hyperextended. Insufficient hamstring muscle strength can also contribute to these injuries.

When an ACL tears, people often experience immediate symptoms. Many report an audible ‘popping’ sound at the time of injury. This is usually followed by excruciating pain and rapid swelling of the knee. People may also feel sensations of instability, or that the knee is “giving way.” Walking can become uncomfortable.

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

PCL Location and Anatomy

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is another vital ligament inside the knee. It is one of the two major cruciate ligaments. The PCL sits behind the ACL.

It connects the back of the shin bone (tibia) to the front of the thigh bone (femur). Specifically, the PCL attaches to the posterior intercondylar area of the tibia. It then runs upward and forward to attach to the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. This diagonal path helps it perform its important role in knee stability.

PCL Function

The PCL plays a crucial role in stabilizing the knee. Its main job is to prevent the shin bone (tibia) from sliding too far backward on the thigh bone (femur). This movement is called posterior tibial translation.

The PCL primarily resists excessive posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur. It serves as the primary stabilizer, preventing posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur. This makes the posterior cruciate ligament a key structure for knee function.

Common PCL Injuries

PCL injuries are less common than ACL injuries. However, they can still happen. Several situations can cause damage to the PCL.

People often injure the PCL by falling onto a bent knee. A hard hit to the front of the knee can also cause injury, like hitting a dashboard in a car accident. Bending the knee too far backward (hyperextension) or dislocating the knee can also tear the PCL. Landing improperly after a jump is another cause.

Certain sports and activities have a higher risk for PCL injuries. These injuries often occur when the knee strikes the ground or an opponent while bent. Sports like football, soccer, and rugby commonly see these types of injuries. Skiing also carries a risk. Traffic-related incidents, such as car accidents, account for a significant number of PCL tears.

Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL)

MCL Location and Anatomy

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is a strong, flat band of connective tissue. It sits on the inner side of the knee. This ligament runs from the medial epicondyle of the femur (thigh bone) to the medial condyle of the tibia (shin bone). It is one of the main collateral ligaments.

The MCL has both superficial and deep layers. The superficial layer is longer and more distinct. The deep layer is shorter and blends with the joint capsule and the medial meniscus. This structure helps stabilize the knee joint.

MCL Function

The primary job of the MCL is to provide stability to the knee. It resists forces that push the knee inward. This type of force is called valgus stress. The medial collateral ligament contributes significantly to this resistance.

It provides up to 78% of the restraining force against valgus (inward pressing) loads on the knee. This function is crucial for preventing the knee from buckling inward. The MCL works with other structures to keep the knee stable during movement.

Common MCL Injuries

MCL injuries are common, especially in sports. They often happen when a force pushes the knee sideways from the outside. This puts stress on the inner side of the knee.

MCL injuries primarily result from three main sprain mechanisms:

Blow to the knee

Contact to the leg or foot (lever-like)

Sliding

Nearly two-thirds of MCL injuries result from direct contact. Approximately one in four MCL injuries occur due to indirect contact. Athletes in contact sports like football or soccer often experience these injuries. A direct hit to the outside of the knee can stretch or tear the MCL.

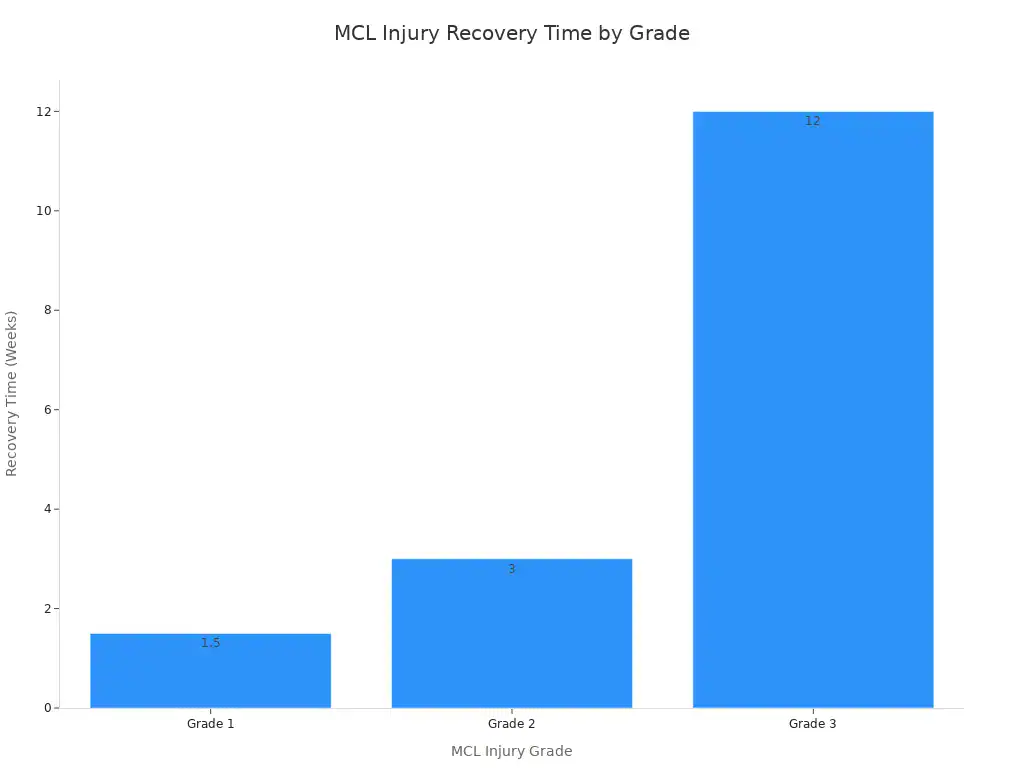

When an MCL injury occurs, people often feel pain on the inside of the knee. Swelling and tenderness are also common. The knee might feel unstable, especially when trying to put weight on it. Recovery time for an MCL injury depends on its severity.

Here is a breakdown of typical recovery times:

MCL Injury Grade | Recovery Time | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

Grade 1 | A few days or couple of weeks | Minor, slight overstretching, pain, swelling, limited use |

Grade 2 | Two to four weeks | More severely overstretched or small tears |

Grade 3 | Up to 12 weeks | Intense tear, often accompanied by other damage (meniscus, ACL), significant instability, may require surgery |

Most MCL injuries heal without surgery. Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) are common treatments. Physical therapy helps restore strength and stability to the knee.

Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

LCL Location and Anatomy

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is a strong, cord-like structure. It sits on the outer side of the knee. This ligament connects the bottom of the thigh bone (femur) to the top of the smaller lower leg bone (fibula). Unlike the MCL, the LCL does not attach to the meniscus. It remains separate from the joint capsule. This distinct location helps it perform its specific role in knee stability.

LCL Function

The LCL provides crucial stability to the knee. Its main job is to resist forces that push the knee outward. Doctors call this “varus stress.” The LCL acts as the primary restraint against varus angulation.

It prevents the lower leg from bowing too far outward. At full extension, the LCL resists approximately 55% of the applied load. The LCL’s role in resisting varus stress increases as the joint bends. It acts as the primary restraint to varus stress at both 5 and 25 degrees of flexion. This makes the LCL a vital component of the knee’s structural integrity.

Common LCL Injuries

LCL injuries often happen due to specific types of force on the knee. A direct impact to the inner side of the knee can push the knee outward, stressing the LCL. This can occur during contact sports or accidents. Other common causes include:

Falling or stumbling and twisting the knee.

Sudden pivots or awkward landings after a jump.

Tripping while running.

Motor vehicle collisions.

Overextension or sudden stretching of the knee.

These injuries can range from a mild stretch to a complete tear of the lateral collateral ligament. People often experience pain on the outside of the knee, swelling, and tenderness. The knee might also feel unstable, especially when walking or putting weight on it.

How Knee Ligaments Work Together

Collective Stability of Knee Ligaments

The four main knee ligaments work together. They ensure the knee joint remains stable. The ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL each play a specific role. Together, these knee ligaments prevent excessive movement.

They also control the knee’s range of motion. For example, the deep medial collateral ligament (dMCL) helps restrain anterior tibial translation. It also controls tibial external rotation. The posterior oblique ligament (POL) resists valgus stress in extension. It also resists tibial internal rotation in extension. It prevents hyperextension with tibial external rotation.

The anterolateral complex (ALC) acts as a secondary stabilizer. It controls anterolateral rotatory laxity (ALRL). When a knee injury affects multiple ligaments, it creates complex stability issues.

For instance, persistent medial instability in combined ACL-MCL injuries increases biomechanical stress on the ACL graft. This raises the risk of graft failure. Persistent MCL deficiency is biomechanically linked to increased loading and strain on the ACL graft.

This can compromise its integrity and long-term outcomes. Failure to address an ALC injury during ACL reconstruction can also increase the risk of ACL graft failure. This happens due to persistent ALRL. The collateral ligaments, including the MCL and LCL, provide crucial side-to-side stability.

Impact of Ligament Injury

Knee ligaments are prone to injury. A knee ligament injury can significantly impact a person’s life. Understanding which ligaments are affected is crucial. The degree of injury also matters. This information helps determine the best treatment plan for recovery.

Many patients with untreated ACL injuries experience functional limitations. This is especially true for demanding physical activities. A study on symptomatic ACL-deficient knees showed that only about one-third of patients improved with rehabilitation.

Another third remained unchanged. One-third worsened. Only 9% returned to full competitive athletics. Patients experiencing ‘giving way’ of the knee, even infrequently, risk developing arthritic changes. A 6-year study of ACL-injured patients found that 63% initially returned to pre-injury sports. However, only 73% of those were still participating by the 6-year mark.

Meniscectomy rates also increased over time. This indicates ongoing risks of meniscal injury. For partial tears (grades 1 or 2) of knee ligament injury, surgery is typically not required. Physical therapy can lead to a full recovery.

This therapy focuses on strengthening quadriceps, hamstring, and gluteal muscles. It also restores normal mobility. Recovery for low-grade sprains may take 2-6 weeks. Complete (grade 3) tears often need knee surgery. This is followed by physical therapy for 4-8 months. Full recovery can take up to 12 months.

This post explained the individual roles of the ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL. These crucial knee ligaments collectively ensure the knee joint’s stability and proper function. Understanding these complex structures helps appreciate the knee joint’s intricate design. It also emphasizes the significance of injury prevention. For any knee pain or suspected injuries, consult medical professionals promptly.