Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) involves a blood clot forming in deep veins. These clots typically appear in the legs, but they can also form in arms, mesenteric, and cerebral veins. Globally, over 10 million cases of DVT and Pulmonary Embolism (PE) are diagnosed annually. This deep venous thrombosis condition carries a significant risk. A nonocclusive thrombus is a partial blockage within a vein. This means some blood flow still occurs.

Despite partial flow, nonocclusive thrombi carry critical risks. The risk of serious complications from DVT is high. This blog focuses on nonocclusive thrombus in DVT. It explains what this thrombus is, why its risks are critical, and how DVT management occurs to reduce this risk.

Key Takeaways

A nonocclusive thrombus is a blood clot in a deep vein that does not fully block blood flow.

Even with partial blockage, these clots carry serious risks, like a piece breaking off and traveling to the lungs (pulmonary embolism).

The clot can grow and completely block the vein, causing more severe symptoms and long-term problems.

Doctors use ultrasound to find these clots, and blood thinners are the main treatment to stop them from growing and causing more harm.

Regular check-ups are important to make sure the treatment works and to prevent new clots from forming.

Understanding Nonocclusive DVT

Defining Nonocclusive Thrombus

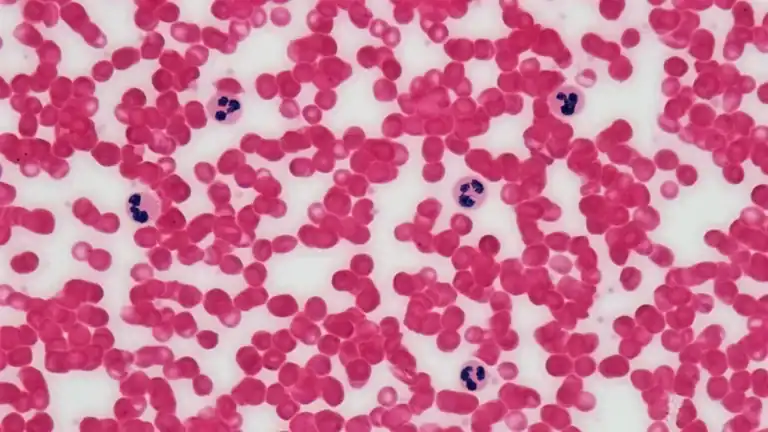

A nonocclusive thrombus is a blood clot that forms inside a deep vein but does not completely block the vessel. This means some blood can still flow past the clot. Doctors often describe this type of clot as having an eccentric shape. It forms an obtuse angle with the venous wall. This partial blockage is a key characteristic of a nonocclusive thrombus in DVT. It allows for continued, though often reduced, blood circulation. The clot typically appears as a mass attached to the vein wall. It does not fill the entire space within the vein.

Differentiating from Occlusive Clots

It is important to understand the difference between a nonocclusive thrombus and an occlusive clot. Both are forms of deep venous thrombosis, but they affect blood flow differently. An occlusive clot completely fills the vein. It stops all blood flow through that vessel. This often leads to more immediate and severe symptoms, such as significant swelling, pain, and discoloration in the affected limb.

A nonocclusive thrombus, on the other hand, allows some blood to pass. This can make its symptoms more subtle or less severe at first. However, this does not mean it carries less risk. In fact, the presence of a nonocclusive thrombus in DVT still poses a significant risk for serious complications.

Doctors use imaging techniques to distinguish between different types of DVT. They look at the clot’s characteristics. For example, they can tell if a clot is acute (new) or chronic (old) based on its appearance.

Thrombus Type | Shape | Echogenicity | Vein Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

Acute | Concentric | Anechoic/Hypoechoic | Dilated |

Chronic | Eccentric | Hyperechoic | Retracted |

An acute DVT often shows a concentric clot that makes the vein look dilated. A chronic DVT, however, often has an eccentric shape and the vein might appear retracted. Both types of clots, whether occlusive or nonocclusive, require careful medical attention due to the inherent risk of complications.

Critical Risks of Deep Venous Thrombosis

Pulmonary Embolism and Embolization Risk

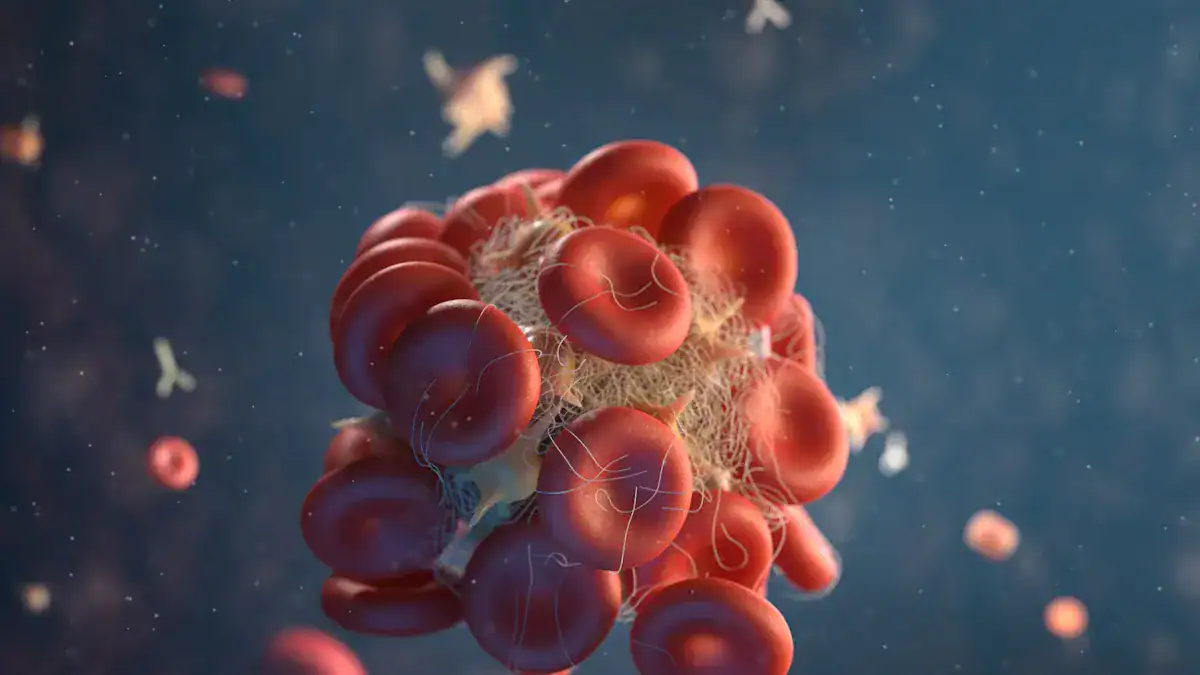

A nonocclusive thrombus in DVT carries a significant risk of pulmonary embolism (PE). PE is a life-threatening complication. It happens when a piece of the clot breaks off and travels to the lungs. Nonocclusive thrombi are particularly prone to fragmentation. This fragmentation allows pieces to migrate. When these fragments reach the lungs, they block blood flow. This blockage can cause severe breathing problems and even death.

Several factors increase the risk of embolization from a nonocclusive thrombus. These include a nonobstructive or free-floating thrombus in the vena cava. Female gender also shows a higher risk. Patients with preoperative clinical pulmonary embolism have an increased risk.

A higher average number of DVT risk factors also contributes to this danger. The use of pharmacomechanical thrombolysis as a single treatment might also increase this risk. Clot fragmentation during flow-mediated thrombolysis can lead to embolization. The size of these fragments depends on blood flow. The disintegration of these fragments, especially large ones, poses a risk for embolization in microvessels. It can even induce life-threatening events like pulmonary embolism.

The danger of thromboembolism extends beyond the lungs. Embolization can occur in other critical sites. For example, a clot fragment could travel to the brain. This can lead to a stroke. If it lodges in the heart, it can cause a heart attack. These thromboembolic events highlight the serious nature of any deep venous thrombosis. The risk of such events makes early diagnosis and treatment crucial.

Thrombus Progression and Occlusion

A nonocclusive thrombus does not always stay partial. It can grow larger. This growth can lead to complete occlusion of the vein. When a clot becomes occlusive, it blocks all blood flow. This causes more severe DVT symptoms. Patients may experience increased pain, swelling, and skin discoloration. This progression also increases the risk of post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS). PTS is a long-term complication.

It causes chronic pain, swelling, and skin changes in the affected limb. The development of PTS significantly impacts a patient’s quality of life. Therefore, preventing thrombus progression is a key goal in managing DVT.

Recurrence Potential

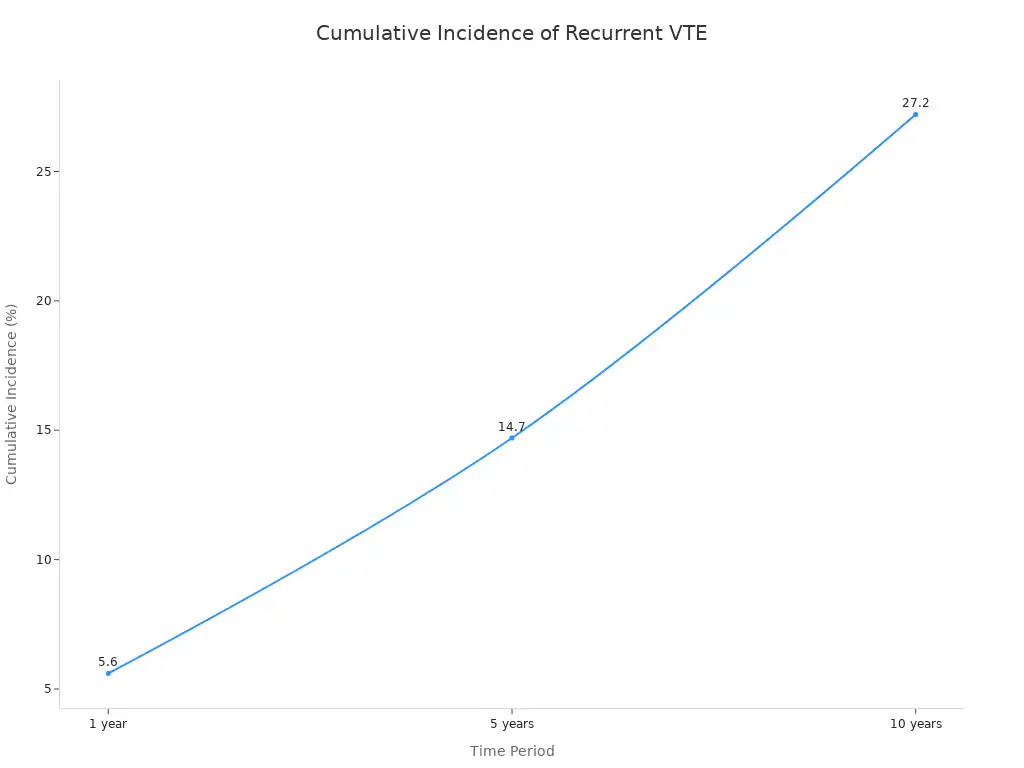

Even after initial treatment, patients with DVT face a significant risk of recurrence. This means a new DVT episode can happen. The potential for future venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major concern. The long-term risk of VTE recurrence after a first-time isolated distal deep vein thrombosis (IDDVT) is high. Recurrence rates are higher for unprovoked IDDVT compared to provoked IDDVT.

The recurrence risk varies. For provoked VTE, the recurrence risk is 3.3% in the first year after stopping anticoagulation. This risk does not increase significantly after 10 years. For unprovoked VTE, the recurrence risk is 10.3% in the first year. This risk increases to more than 30% after 10 years.

The cumulative incidence of recurrent VTE also shows this trend.

Time Period | Cumulative Incidence of Recurrent VTE |

|---|---|

1 year | 5.6% (95% CI, 3.7-8.4) |

5 years | 14.7% (95% CI, 11.1-19.4) |

10 years | 27.2% (95% CI, 21.1-34.5) |

These statistics highlight the ongoing risk. Patients need careful monitoring and management. This helps reduce the chance of another DVT or PE. The overall burden of venous thromboembolism remains high due to this recurrence.

Diagnosing Nonocclusive DVT

Recognizing Subtle Symptoms

Diagnosing a nonocclusive thrombus in dvt presents significant challenges. Its symptoms are often subtle or atypical compared to a fully occlusive clot. This makes identification particularly difficult. Approximately half of individuals with DVT may not exhibit any noticeable signs or symptoms. This lack of clear indicators increases the diagnostic risk. For example, a 77-year-old male with a spinal cord injury showed an atypical presentation. He had persistent fever and high inflammatory markers.

He lacked typical infection symptoms. Imaging later revealed a nonocclusive thrombus in his common femoral and superficial femoral veins. Anticoagulation therapy resolved the thrombus, fever, and inflammatory markers. This case highlights how nonocclusive DVT often mimics other conditions. This makes early detection crucial to reduce the risk of complications. Doctors must consider DVT even with unusual symptom patterns.

Imaging for Nonocclusive Thrombus

Doctors use specific imaging techniques to diagnose DVT. Duplex ultrasound is the primary method. It visualizes the clot and assesses its nonocclusive nature. This ultrasound shows blood flow and clot characteristics. It helps determine if the clot partially blocks the vein. The technique also helps differentiate acute from chronic DVT. Other diagnostic methods exist. These include venography or CT venography. They provide detailed images of the veins. These methods are useful when ultrasound results are unclear or for complex cases.

When doctors suspect chronic DVT, they look for specific signs. These include an echogenic, nonocclusive, or discontinuous thrombus. Such findings often require serial testing. This helps monitor the clot’s stability and progression. Effective DVT screening helps identify these clots early. This reduces the risk of further complications. Regular DVT screening is important for high-risk patients. It helps manage the deep venous thrombosis effectively. Early diagnosis of symptomatic deep vein thrombosis is vital for patient outcomes. It guides treatment decisions and minimizes long-term risk.

Managing Nonocclusive Thrombus Risks

Anticoagulation Therapy

Managing a nonocclusive thrombus in DVT primarily involves anticoagulation therapy. Blood thinners play a crucial role. They prevent the clot from growing larger. They also reduce the risk of embolization, such as a pulmonary embolism (PE).

Doctors typically prescribe these medications for several months. The exact duration depends on the patient’s specific risk factors and the nature of the deep venous thrombosis. This treatment helps prevent serious thromboembolic events. It is a key part of any thromboprophylaxis protocol. Effective thromboprophylaxis is vital for patient safety. It reduces the overall risk of complications.

When Intervention is Considered

Most nonocclusive DVT cases respond well to anticoagulation. However, some situations may require more aggressive interventions. These cases are rare. For example, if a patient experiences recurrent DVT despite adequate anticoagulation, or if the clot poses an immediate, severe risk of pulmonary embolism, doctors might consider other options.

These could include catheter-directed thrombolysis or surgical removal of the clot. Such interventions aim to quickly reduce the clot burden and lower the risk of severe thromboembolism. A robust thromboprophylaxis protocol is always in place, especially for critically ill trauma patients, where early thromboprophylaxis is crucial to mitigate the high risk of VTE. This proactive prophylaxis helps manage the overall risk.

A nonocclusive thrombus in DVT, despite allowing some blood flow, is a serious medical condition with critical risks. Patients face a significant risk of pulmonary embolism and other embolization events. This thromboembolism can also grow, becoming fully occlusive. Early diagnosis and consistent medical management, like anticoagulation, are crucial for mitigating these risks. Proactive treatment improves patient outcomes and prevents life-threatening venous thromboembolism complications. Awareness helps manage the overall risk of venous thromboembolism.