The vertebral column is divided into five distinct regions. This complex structure, often visualized in a Spine Diagram, comprises 33 individual vertebrae. These include 24 movable vertebrae, plus the fused sacrum and coccyx in adults. Each region of the spine plays a specific role in overall spinal function. Understanding these vertebral regions is fundamental to grasping the full anatomy of the spine. The distinct sections are the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal areas. Each vertebral segment contributes to the column’s strength and flexibility.

Key Takeaways

The spine has five main parts: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, and coccyx. Each part has special vertebrae that help the spine move and support the body.

Intervertebral discs are like cushions between the vertebrae. They help the spine bend and twist. They also absorb shock to protect the spine.

The spine has natural curves, like an ‘S’ shape. These curves help balance the body. They also help the spine absorb shock and move well.

Each vertebra has a body and an arch. The body carries weight. The arch protects the spinal cord. Ligaments connect vertebrae and keep the spine stable.

Problems like herniated discs or disc degeneration can cause pain. These issues happen when discs wear out or get injured. Keeping the spine healthy is important.

Spinal Regions: A Map of Your Spine

The vertebral column is a complex structure. It provides support and flexibility to the body. This section offers a detailed map of your spine, exploring its distinct regions. Understanding each part of the vertebral column helps one appreciate its overall function. The entire spinal column works together to protect the spinal cord and allow movement.

Cervical Spine

The cervical spine forms the neck region. It contains seven vertebrae, labeled C1 through C7. This part of the vertebral column supports the head and allows for a wide range of motion. The first two cervical vertebrae are unique. C1, known as the Atlas, has a ring-like shape and lacks a vertebral body. This design allows for significant head movement. C2, called the Axis, features a prominent upward projection. This projection, known as the dens, extends into the Atlas. It acts as a stable pivot point for the Atlas’s rotation, enabling head turning.

Thoracic Spine

The thoracic spine is the middle section of the vertebral column. It consists of twelve thoracic vertebrae, labeled T1 through T12. These vertebrae are intermediate in size. They progressively increase in size as they move towards the lumbar spine. Thoracic vertebrae have distinct features. Their vertebral bodies are heart-shaped. They also have special facets on their sides. These facets connect with the heads of the ribs. The spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae are long and point downwards. This provides extra protection for the spinal cord.

Lumbar Spine

The lumbar spine makes up the lower back. It typically has five movable vertebrae, numbered L1 through L5. These vertebrae are the largest in the vertebral column. They bear most of the body’s weight. Lumbar vertebrae have several distinguishing features. They possess large, kidney-shaped vertebral bodies. Their spinous processes are short and thick. These processes project almost horizontally. The articular facets on lumbar vertebrae are vertical. This arrangement allows for significant flexion and extension movements in the lower back. The L5 vertebra has the largest body and transverse processes among all vertebrae.

Sacrum and Coccyx

The sacrum and coccyx form the base of the vertebral column. The sacrum consists of five fused vertebrae. It is a large, triangular bone located at the base of the spine. It connects to the pelvis. This connection provides stability to the pelvic girdle. The coccyx, or tailbone, is below the sacrum. It consists of three to five small, fused vertebrae. These bones are the very end of the spinal column. They provide minor support and attachment for some muscles. This complete map of your spine shows how each vertebra contributes to the strength and flexibility of the entire spine.

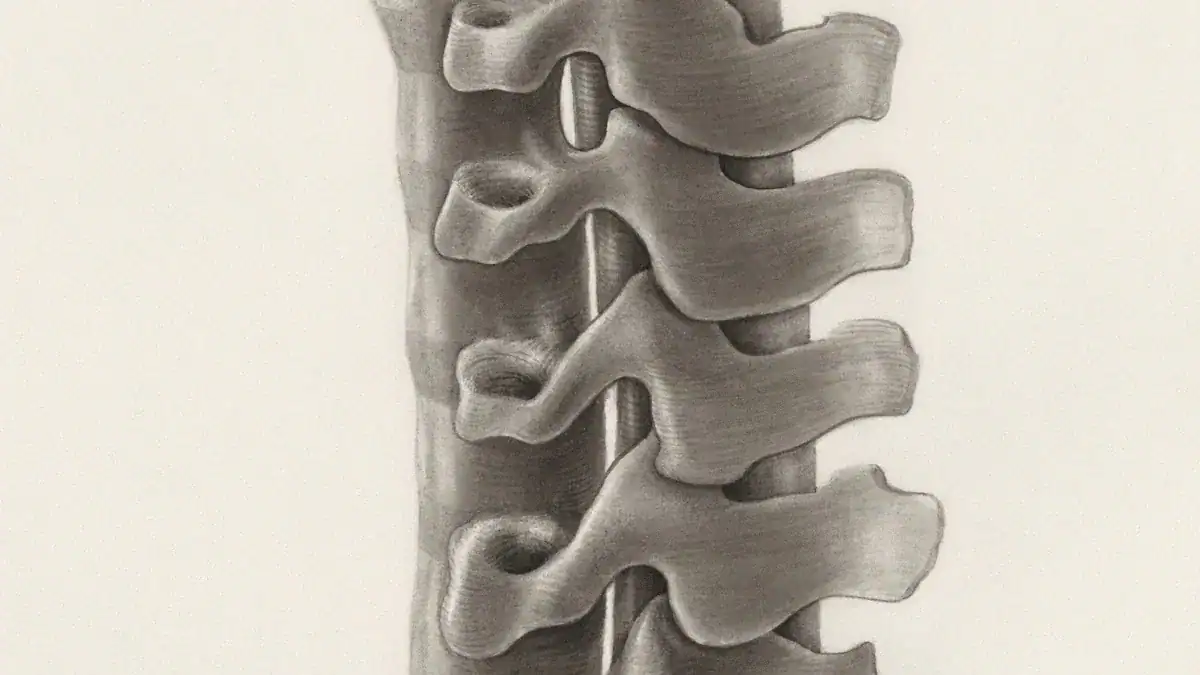

Vertebra Structure & Function

The vertebral column is a marvel of biological engineering. It provides both support and flexibility. Each vertebra in this column has a specific design. This design allows it to perform its role effectively. Understanding the general structure of a vertebra helps one appreciate the entire spinal system.

Vertebra Components

Each vertebra in the vertebral column contributes to the overall strength and flexibility of the spinal column. A spine diagram clearly illustrates these components.

Vertebral Body: This is the anterior, weight-bearing part of the

vertebra. Its size increases in the lowervertebral columnto support more weight. Its superior and inferior surfaces have hyaline cartilage.Intervertebral discs separate adjacent bodies. Thevertebralbody, also known as the centrum, bears the load of thevertebral column. Its upper and lower surfaces serve as attachment points for theintervertebral discs.Vertebralendplates, part of thevertebralbody, contain the adjacentdiscs. They distribute applied loads evenly. They also provide anchorage for the collagen fibers of thedisc. These endplates function as a semi-permeable interface for the exchange of water and solutes.Vertebral Arch: This arch is located posteriorly and laterally. It combines with the

vertebralbody to form thevertebralforamen. The alignment of these foramina creates thevertebralcanal, which houses thespinal cord. Thevertebralarch also features several bony projections for muscle and ligament attachment:Spinous processes: A single process extends posteriorly from the center of the arch.

Transverse processes: Two processes extend laterally and posteriorly. They articulate with ribs in the

thoracicregion.Pedicles: They connect the

vertebralbody to the transverse processes.Lamina: They connect the transverse processes to the spinous process.

Articular processes: They form joints between

vertebrae. They are located where the laminae and pedicles meet.

Regional Vertebra Variations

The vertebrae in different spinal regions show unique characteristics. These variations allow the vertebral column to perform specialized functions. For example, cervical vertebrae are small. They allow for extensive head movement. Thoracic vertebrae connect to ribs. Lumbar vertebrae are large. They support significant weight. The vertebral column adapts its structure. The entire spine benefits from these regional specializations.

Feature | Lumbar Vertebrae | Thoracic Vertebrae |

|---|---|---|

Size | Large | Smaller |

Vertebral Body | Large, robust, strong weight-bearing structures | Less robust |

Costal Facets | Absent | Present (for rib articulation) |

Superior Articular Facets | Directed medially, mild posterior angle | Directed posteriorly |

Mammillary Processes | Present on lateral surface of superior articular processes | Absent |

Transverse Processes | Generally thin and long (except L5) | Prominent, short, stout (lower region) |

This table highlights key differences. Lumbar vertebrae have large, robust vertebral bodies. They handle the body’s weight. Thoracic vertebrae have costal facets. These facets allow them to articulate with the ribs. This articulation forms the rib cage. The cervical vertebrae, especially C1 and C2, have highly specialized structures. C1 (Atlas) lacks a vertebral body. C2 (Axis) has the dens. These unique features enable head rotation.

Spinal Ligaments

The vertebral column relies on strong ligaments for stability. These ligaments connect vertebrae and help protect the spinal cord and spinal nerves. They also limit excessive movement. The vertebral column maintains its integrity through these strong connections.

Ligament Name | Primary Function |

|---|---|

Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) | Runs down the front of the |

Posterior Longitudinal Ligament (PLL) | Located inside the |

Ligamentum Flavum | Connects the laminae of adjacent |

Interspinous Ligament | Connects the spinous processes of adjacent |

Supraspinous Ligament | Runs along the tips of the spinous processes from the seventh |

Intertransverse Ligament | Connects the transverse processes of adjacent |

Iliolumbar Ligament | Connects the transverse process of the fifth |

Sacroiliac Ligaments (Anterior, Posterior, Interosseous) | Connect the sacrum to the ilium. They form the sacroiliac joint. These are very strong ligaments. They provide stability to this joint. This is crucial for weight-bearing and movement. |

Sacrotuberous Ligament | Connects the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity. It helps stabilize the pelvis. It limits rotation of the sacrum. |

Sacrospinous Ligament | Connects the sacrum to the ischial spine. It also helps stabilize the pelvis. It forms part of the boundaries of the greater and lesser sciatic foramina. |

The anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) primarily limits excessive extension (backward bending) of the vertebral column. It maintains spinal stability. It prevents hyperextension. It supports the anterior aspect of the vertebral column. This action protects the spinal cord and spinal nerves from compression or injury due to overextension.

It maintains spinal integrity during movements that stress the ligament. Spinal ligaments, including the anterior longitudinal ligament, provide spinal stability. They work with musculature during physiological loading. They protect the spinal cord from injury. The anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) stabilizes the intervertebral discs. It prevents hyperextension of the vertebral column.

Intervertebral Discs: Structure & Role

Intervertebral discs are crucial components of the vertebral column. They sit between each vertebra, acting as cushions and enabling movement. These specialized structures contribute significantly to the flexibility and strength of the entire spinal column. Understanding their intricate design helps one appreciate their vital role in spinal health.

Annulus Fibrosus

The annulus fibrosus forms the tough, outer ring of the intervertebral disc. It has a laminate structure, consisting of 15 to 25 concentric layers called lamellae. These layers are primarily made of type I collagen fibers. The fibers alternate in angle, ranging from 30° at the periphery to 44° at the center, relative to the disc’s transverse plane. This arrangement gives the annulus fibrosus its strength and anisotropic mechanical properties.

The outer annulus is tougher and less flexible. It contains densely packed type I collagen fibers, making up 70% of its dry weight. The inner annulus is softer and less dense. It has a greater fibrocartilaginous component, primarily composed of type II collagen fibers. The inner annulus also shows a higher ratio of type II to type I collagen. Its proteoglycan concentration increases from 10% to 30% from the outer to the inner annulus.

Chemically, the annulus fibrosus contains 65–90% water by wet weight. It also has 50–70% collagen and 10–20% proteoglycans by dry weight. Noncollagenous proteins like elastin are also present.

The outer annulus mainly contains type I collagen, accounting for about 90% of the collagens in the intervertebral disc. Smaller amounts of collagen types III, V, and VI are also present. Elastic fibers make up only 2% of the annulus fibrosus dry weight, with a higher density in the outer region. Towards the inner annulus fibrosus, the structure transitions to one enriched with type II collagen and a higher content of proteoglycans such as aggrecan, biglycans, and lumican. This results in a less organized fibrous structure.

The annulus fibrosus plays a crucial role in anchoring the intervertebral disc to the vertebrae. Its peripheral fibers merge with the longitudinal ligaments, securing the disc’s position. The annulus fibrosus resists both tensile and compressive stresses. It contributes significantly to the disc’s overall mechanical integrity.

Nucleus Pulposus

The nucleus pulposus is the gelatinous, central core of the intervertebral disc. It acts as the primary cushion for the spinal column. Its unique composition allows it to perform this function effectively.

Component | Description |

|---|---|

Water | Accounts for 70-90% of the nucleus pulposus’s wet weight. This high water content is crucial for its hydraulic properties and ability to withstand compressive forces. |

Proteoglycans | Primarily aggrecan, which is responsible for the osmotic properties of the nucleus pulposus. Aggrecan molecules attract and retain water, contributing to the turgor pressure within the disc. |

Collagen Fibers | Predominantly Type II collagen, forming a network that provides structural integrity and helps to contain the proteoglycan-water gel. Type I collagen is also present in smaller amounts, particularly in the outer regions. |

Chondrocytes | Specialized cells that produce and maintain the extracellular matrix components (proteoglycans and collagen). Their density is relatively low compared to other connective tissues. |

Non-collagenous Proteins | Various proteins that play roles in cell signaling, matrix organization, and tissue maintenance, though they constitute a smaller percentage of the overall composition. |

Elastin | Present in small quantities, contributing to the elasticity of the tissue. |

Glycoproteins | Involved in cell adhesion and interaction with matrix components. |

Other Cells | Fibroblasts and notochordal cells (more prominent in younger individuals) can also be found. |

Ions and Solutes | Various inorganic ions and small organic molecules that contribute to the osmotic balance and cellular function. |

The nucleus pulposus’s high water content and proteoglycan concentration give it a gel-like consistency. This allows it to effectively cushion and distribute compression loads. These loads then transfer to the surrounding annulus fibrosus, which is under circumferential tension.

Disc Function

Intervertebral discs are central to the spine’s function. They provide flexibility, support, and shock absorption. Without these discs, spinal movement would be severely limited. The nucleus pulposus, with its high water content, acts as the primary shock absorber.

It redistributes mechanical forces during movement. The annulus fibrosus, the tough outer layer, provides structural integrity. Its concentric fibrocartilaginous sheets, arranged in alternating directions, resist tensile forces while maintaining flexibility. These layers work together to confine the nucleus pulposus. They protect the disc from excessive strain, contributing to both strength and flexibility.

The intervertebral disc permits various movements between vertebral bodies. These include:

Axial compression/distraction

Flexion/extension

Axial rotation

Lateral flexion

Disc thickness generally increases from the top (rostral) to the bottom (caudal) of the vertebral column. The thickness of the discs relative to the size of the vertebrae is highest in the cervical and lumbar regions. This reflects the increased range of motion found in those areas. The intervertebral disc is part of a ‘three-joint complex’. This complex, along with facet joints and soft tissues, contributes to motion, weight bearing, and flexibility of the entire spine.

Common Disc Issues

Intervertebral discs, despite their resilience, can develop various issues. These problems often lead to pain and reduced mobility.

A herniated disc occurs when one of the cushions between the vertebrae in your spinal column tears or leaks. This can happen due to natural wear and tear or injury. A herniated disc is a fragment of the disc nucleus that is pushed out of the annulus into the spinal canal through a tear or rupture. This displacement can press on spinal nerves, often causing severe pain. Other names for a herniated disc include:

Bulging disk

Slipped disk

Ruptured disk

Protruding disk

This condition puts pressure on the spinal cord and irritates spinal nerves. It leads to pain, numbness, and weakness.

Disc degeneration is another common issue. Several factors contribute to this process:

Age: This is the most common risk factor. Spinal discs lose water and structural integrity with aging. This increases susceptibility to rupture and herniation.

Genetic predisposition: Degenerative disc disease often runs in families, suggesting a genetic component.

Mechanical stress: Professions involving repeated stresses (e.g., carpentry) or prolonged inactivity (e.g., long-haul trucking) can lead to disc degeneration.

Obesity: Excess body weight places additional strain on the spine. This increases the risk of degenerative disc disease.

Inadequate nutrition: Poor blood supply to spinal discs, possibly due to age or conditions like diabetes, can hinder nutrient delivery.

Smoking: This habit appears to accelerate the aging process of discs, making them more prone to degeneration.

As people age, the water content in their discs decreases from approximately 80%. This leads to desiccation and thinning. Decades of normal daily activities like standing, sitting, walking, bending, and twisting can weaken and wear down the outer parts of the discs. Sports, while beneficial for health, can also place stress on spinal discs. Injured discs struggle to heal due to insufficient blood supply. Degenerative changes, such as disc height loss, primarily affect flexibility in flexion/extension and axial rotation. This explains the higher correlation of disc degeneration with the range of motion in these planes. The minor effects of disc degeneration in lateral bending may be due to the presence of uncovertebral joints. These joints significantly contribute to lateral bending flexibility of the cervical spine.

Spinal Curves & Importance

The human vertebral column is not straight. It features natural curves that give it an S-shape. These curvatures of the vertebral column are essential for balance, shock absorption, and flexible movement. They help the vertebral column distribute weight evenly and protect the spinal cord. Each curve plays a specific role in the overall function of the vertebral column.

Cervical Lordosis

Cervical lordosis is the natural inward curve of the neck. This curve helps support the head and allows for a wide range of motion. The normal range for cervical lordosis is between 20 and 40 degrees. A clinically normal range is often identified as 31 to 40 degrees. This natural lordotic curvature of the cervical spine is an ideal posture. It protects the upper spinal cord, which is crucial for nerve signal transmission. Maintaining this curve is essential for preventing chronic pain and degenerative diseases in the vertebral column.

Thoracic Kyphosis

Thoracic kyphosis is the outward curve of the upper back. This curve gives the thoracic spine its characteristic rounded shape. It helps protect the heart and lungs. The normal kyphosis angle varies by age and sex. Younger individuals typically have a range of 20 to 40 degrees. Older women might show 48 to 50 degrees, and older men around 44 degrees. This curve is vital for the structural integrity of the vertebral column.

Lumbar Lordosis

Lumbar lordosis is the inward curve of the lower back. This curve helps maintain the body’s center of gravity. It is crucial for a healthy gait. This curve in the lumbar spine also facilitates strength and flexibility. It ensures even distribution of mechanical stress during movement. The lumbar vertebrae are designed to support significant weight, and this curve helps manage that load effectively.

Curve Abnormalities

Sometimes, the natural curves of the vertebral column become exaggerated or flattened. These changes in spinal alignment can lead to health problems.

Excessive Kyphosis (Hyperkyphosis): This is an overly rounded upper back. It means the thoracic curve exceeds 40 degrees. Excessive kyphosis can cause pain and dysfunction in the shoulder and lower back. It increases the risk of fractures. It also links to increased mortality rates, especially from pulmonary causes. People with hyperkyphosis often have difficulties with daily activities and poorer balance.

Excessive Lordosis (Hyperlordosis): This is an exaggerated inward curve in the lower back or neck. It creates a noticeable arch in the lower back. This condition can cause lower back pain and muscle tightness. It may limit the range of motion in the lower back and hips. In severe cases, it can lead to muscle weakness or numbness in the legs. This abnormal alignment can also increase the risk of long-term discomfort and complications like arthritis.

Maintaining proper spinal alignment is key for overall health and function of the vertebral column.

This blog explored the intricate spine anatomy. It detailed the distinct regions of the vertebrae, highlighting their individual structures and regional variations. Each vertebra forms part of the vertebral column. The intervertebral disc provides crucial flexibility and shock absorption for the vertebral column. Ligaments offer stabilizing function.

Natural spinal curves are also vital. This spine diagram illustrates how each vertebra, intervertebral disc, and ligament works together. The entire vertebral column ensures spinal integrity, movement, and overall well-being. The spinal cord and spinal nerves depend on this robust vertebral column. Understanding this complex anatomy empowers individuals. They can make informed choices for their spinal health. Each disc and vertebra contributes to the column’s strength. The vertebral column protects the spinal cord and spinal nerves.